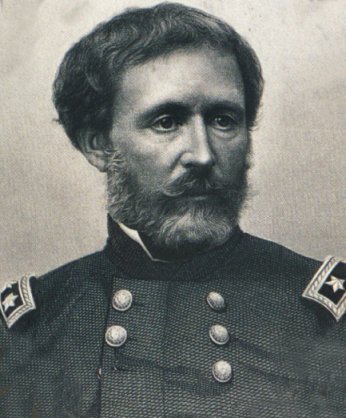

US General John C. Frémont: “In late August [1861] the diffuse feeling of unhappiness with the Lincoln administration found a focus. General … Frémont, named commander of the Department of the West, with headquarters in St. Louis, took drastic steps to defeat a Confederate invasion in southwestern Missouri and end widespread guerilla warfare elsewhere. Proclaiming martial law in the entire state of Missouri, Frémont announced that civilians bearing arms would be tried by court-martial and shot if convicted and that slaves of persons who aided the rebellion would be emancipated. Frémont’s proclamation, issued without consulation with Washington, clearly ran counter to the policy Lincoln had announced in his inaugural address of not interfering with slavery and against the recently adopted Crittenden resolution pledging that restoration of the Union was the only aim of the war. It also violated the provisions of the Confiscation Act, which established judicial proceedings to seize slaves used to help the rebel army. Lincoln saw at once that Frémont’s order must be modified. He directed the general to withdraw his threat to shoot captured civilians bearing arms. “Should you shoot a man, according to the proclamation, the Confederates would very certainly shoot our best man in their hands in retaltion,” he admonished Frémont; “and so, man for man, indefinitely.” The President viewed Frémont’s order to liberate slaves of traitorous owners as even more dangerous. Such action, he reminded the general, “will alarm our Southern Union friends, and turn them against us – perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky.” He asked Frémont to modify his proclamation. … Frémont took [Lincoln’s]letter as an undeserved rebuke. … The general, who had made is reputation as pathmaker of the Western trails to Florida, was never able to find his way across the Missouri political terrain. He quarelled with everybody. … To ineptness, charges of fraud and corruption in the Department of the West were added, though nobody accused Frémont of using his command for personal gain. … Frémont was relieved from command on November 2. The Frémont imbroglio caused an immense turmoil throughout the Union. In the border slave states, just as Lincoln predicted, Frémonts proclamation dealt a heavy blow to Unionist sentiment. … Frémont’s decree came at the worst possible time, when the legislature [of Kentucky] was about to abandon the policy of neutrality for Kentucky. … By overruling the most offensive parts of Frémont’s edict, Lincoln saved the state for the Union. In the North the reaction was exactly the opposite. Frémont’s order aroused a public that was already tired of the war and demanded decisive steps to end it. All the mayor newspapers approved it …” (D.H. Donald, Lincoln [New York 1996], p. 314-317)