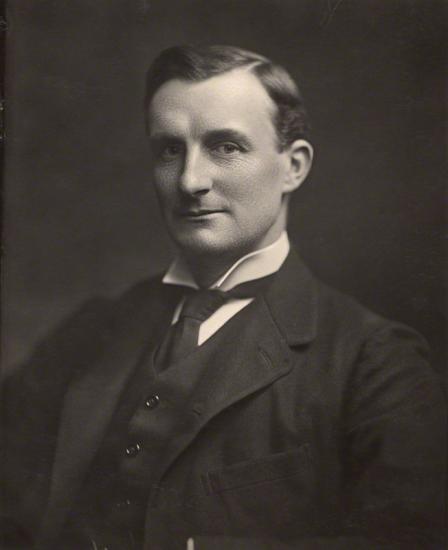

Sir Edward Grey. British Foreign Secretary 1905-1916.

“The repercussions of the assassination at Sarajevo intruded into Anglo-Russian relations only slowly. During the July crisis [1914], Grey had followed the policy of close collaboration with Germany that had worked so successfully during the first Balkan crisis. It was not until 24 July, when Buchanan informed Grey of Russia’s hope that Britain would ‘express strong reprobration’ at Austria-Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia, that much thought seems to have been given to Russia outside of the negotiations about Persia. … the foreign secretary remained largely aloof from his advisers at the Foreign Office and the issue of war or peace was decided in the Cabinet. There was some reflection of them, however, when Grey made his dramatic speech in the House of Commons on 3 August [1914], at which time the foreign secretary briefly alluded to the fact that if Britain remained neutral in the war the ententes with France and Russia would be at an end, regardless of the outcome of hostilities. The impact of Russia in that venue and on the British decision to go to war is a contentious point. On the one hand, Keith Wilson [The Policy of the Entente (Cambridge, 1985)] argues that Britain went to war to protect her interests in Asia from the consequences of standing aloof from the war – in short that the maintenance of good Anglo-Russian relations was the determining factor in Grey’s advocacy of war. On the other hand Zara Steiner [Britain and the origins of the First World War (London, 1977)] believes that Grey attempted to pursue an even-handed policy, but in the final analysis was pushed by German actions into siding with the entente. Looked at from the perspective of Anglo-Russian relations in the period from 1894 to 1914, there can be no doubt that Steiner’s argument is correct. … Grey’s willingness to renegotiate the Anglo-Russian Convention [of 1907] in 1914 was not a sign that the foreign secretary was aiming at some sort of Anglo-Russian alliance. Rather, it was an admission that the patch placed in 1907 on the long-standing running sore of Anglo-Russian enmity was only temporary.” (K. Neilson, The British and the last Tsar. British policy and Russia, 1894-1917 [New York 1995], p. 339-340)