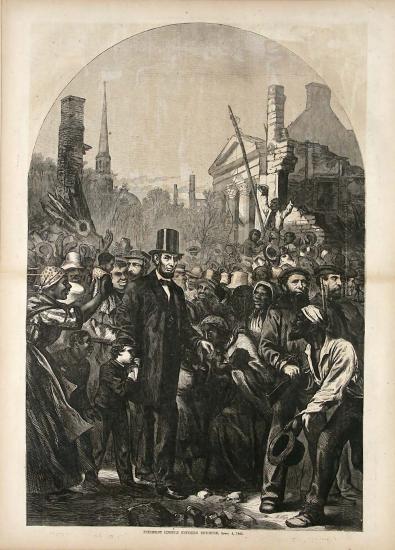

Abraham Lincoln en zijn zoon Tad in Richmond (1865)

“[In 1850 Lincoln delivered an eulogy on the Kentucky statesman Henry Clay. He said that Clay]”ever was, on principle and in feeling, opposed to slavery.” Because Clay recognized that it could not be “at once eradicated, without producing a greater evil”, he supported the efforts of the American Colonization Society to transport African-Americans back to Africa and served for many years as president of that organization. Endorsing Clay’s views on colonization, Lincoln revealed a change in his own attitude toward slavery. He had all along been against the peculiar institution, but it had not hitherto seemed a particularly important or divisive issue, partly because he had so little personal knowledge of slavery. But in Washington his strongly antislavery friends in Congress, like Joshua R. Giddings and Horace Mann, helped him see that the atrocities that occurred every day in the national capital were the inevitable results of the slave system. … Lincoln looked for a rational way to deal with the problems caused by the existence of slavery in a free American society, and he believed he had found it in colonization. … he became convinced that transporting African-Americans to Liberia would defuse several social problems. By relocating free Negroes from the United States – and, at least initially, all those transported were to be freedmen – colonization would remove what many white Southerners considered the most disruptive elements in their society. Consequently, Southern whites would more willingly manumit their slaves if they were going to be shipped off to Africa. At the same time, Northeners would give more support for emancipation if freedmen were sent out of the country; they would not migrate to the free states where they would compete with white laborers. Moreover, colonization could elevate the status of the Negro race by proving that blacks, in a separate, self-governing community of their own, were capable of making orderly progress in civilization. Thus, Lincoln thought, voluntary emigration of the blacks – and, unlike some other colonizationists, he never favored forcible deportation – would succeed both “in freeing our land from the dangerous presence of slavery” and “in restoring a captive people to their long-lost father-land, with bright prospects for the future.” The plan was entirely rational – and wholly impracticable. American blacks, nearly all of whom were born and raised in the United States, had not the slightest desire to go to Africa: Southern planters had no intention of freeing their slaves; and there was no possibility that the Northern states would pay the enormous amount of money required to deport and resettle millions of African-Americans. From time to time, even Lincoln doubted the colonization scheme would work,… [but he] persisted in his colonization fantasy until well into his presidency. … Lincoln’s persistent advocacy of colonization served an unconscious purpose of preventing him from thinking too much about a problem that he found insoluble. He confessed that he did not know how slavery could be abolished. … For a man with a growing sense of urgency about abolishing, or at least limiting slavery, who had no solution to the problem and no political outlet for making his feelings known, colonization offered a very useful escape.” (D.H. Donald, Lincoln [New York 1996], p. 165-167) “[During the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858 Lincoln said in Charleston: “I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races … I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people.” “There is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality,” he went on to add. It represented Lincoln’s deeply held personal views, which he had expressed before. Opposed to slavery throughout his life, he had given little thought to the status of free African-Americans. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was not personally hostile to blacks … [b]ut he did not know whether they could ever fit into a free society, and, rather vaguely, he continued to think of colonization as the best solution to the American race problem.” (id. p. 221)