Het Hof is op grond van het voorgaande van oordeel dat de beklaagde [voormalig keizer van Duitsland Wilhelm II] zowel formeel als feitelijk de mogelijkheid had om de schending van de Belgische neutraliteit te voorkomen. Hij heeft willens en wetens nagelaten om deze mogelijkheid te benutten. Uit de omstandigheid dat hij het opperbevel voerde over de legereenheden die de aanval op België uitvoerden, moet integendeel worden afgeleid dat de schending van de Belgische neutraliteit onder zijn leiding plaatsvond. Dat de beklaagde het niet alleen voor het zeggen had, zoals door de verdediging is betoogd, doet hieraan niets af.” (H. Andriessen e.a., Het proces tegen Wilhelm II. Een vonnis over de schuld van de Duitse keizer aan WO I [Tielt 2016], p. 409)

Stadhouder-koning Willem III (1650-1702) “De Leidse historicus Roorda heeft Willem een ‘raadselachtige man’ genoemd. Dat is een juiste karakterisering aangezien Willem een uiterst gesloten, weinig spontane en terughoudende persoon was, die zijn ware gevoelens slechts aan een heel kleine kring van intimi openbaarde. … Dit gevoelloos ogende en weinig toegankelijke karakter maakte hem in de ogen van buitenstaanders tot een koude kikker. Het tegendeel was echter waar. De prins was in wezen een gevoelig, emotioneel mens, die er echter alles aan deed zijn gevoelens verborgen te houden. … Over de vraag of Willem III homoseksueel was, is al veel geschreven. Noordam, die in zijn studie over de geschiedenis van de homoseksualiteit in Nederland een apart hoofdstuk aan Willem III heeft gewijd, wijst erop, dat de term homoseksualiteit pas in de negentiende eeuw is ontstaan. Hij reserveert deze term voor mensen die zich bewust zijn van hun homoseksualiteit of uit wier gedrag blijkt dat ze een homoseksuele identiteit bezitten. Noordam gebruikt de term sodomiet om aan te geven dat iemand homoseksuele handelingen verricht. … In het leven van Willem onderscheidt Noordam drie levensfasen waarin de prins steeds verder opschoof in de richting van een homoseksueel in de twintigste-eeuwse betekenis, al moet hij toegeven, dat het absolute bewijs ontbreekt. Aanvankelijk was ik niet overtuigd van het feit, dat Willem III homoseksuele betrekkingen heeft onderhouden. Ik deelde het standpunt van Baxter, die beweert, dat Willem III het zo druk had met andere werkzaamheden dat hij geen tijd had voor seksuele relaties. Toch had ik al in 1988 bij de uitgave van een verslag over de tocht van Willem III naar Engeland van 1670-1671 … een citaat daaruit gebruikt om Willems geringe belangstelling voor vrouwen aan de orde te stellen. Iedereen was te spreken over de prins behalve ‘de Engelsche Dames omdat hij niet wercks genoegh van haer en maeckte.’ Deze mening werd meer dan 25 jaar later nog eens bevestigd door Liselotte van de Palts, een achternicht van Willem III. In een brief van 26 aug. 1696 schreef ze, dat Willem III nauwelijks aandacht aan vrouwen besteedde en bijzonder weinig met hen op had. Volgens Noordam is het opvallend dat Willem III en Mary Stuart II geen kinderen kregen en dat Willem III, voor zover bekend, ook geen bastaarden verwekte. … Pas in 1689 kwamen de geruchten over sodomie op gang in Engeland. Daarvoor, in 1682, werd Willem III zo vaak bezocht door een zekere ritmeester van Dorp, dat Huygens jr., de secretaris van Willem III, twee keer bij Baarsenburg, de kamerdienaar, informeerde naar het doel van deze bezoeken. Baarsenburg had zich op de vlakte gehouden, maar wel gezegd, dat de bezoeken al enige tijd onregelmatig plaatsvonden en soms een half uur duurden. De verdenking dat de koning sodomie pleegde, groeide in de jaren ’90. Mij lijkt het inmiddels waarschijnlijk, dat Willem III homoseksuele relaties had, maar dat hij die activiteit goed verborgen wist te houden. Dat is niet zo vreemd bij een man die de karaktertrek ‘fort dissimulé’ bezat.” (Wout Troost, Stadhouder-koning Willem III, een politieke biografie [Hilversum 2001], p. 35-37) [Opvallend is tevens het tamelijk grote aantal ‘sodomieten’ in Willems directe familie: Henry Darnley, zijn betovergrootvader, Jacobus I van Engeland en Schotland, zijn overgrootvader, Karel I van Engeland en Schotland, zijn grootvader en Philips van Orléans, zijn moeders neef. (ABdH)]

“Äccording to almost all written sources, the main income of the Crimean Khanate came from raids upon the territories of adjacent countries and from the trade in slaves captured during these military campaigns. The first major Tatar raid for captives took place in 1468 and was directed into Galicia. According to some estimates, in the first half of the seventeenth century the number of the captives taken to the Crimea was around 150,000-200,000 persons. About 100,000 of them were captured in the period between 1607 and 1617. The Crimean Tatars invaded Slavic lands 38 times from 1654 to 1657; 52,000 people were seized by the Tatars in the spring of 1655 in the course of a raid into the territory of Ukraine and Southern Russia. The number of Tatar raids seems to have diminished in the eighteenth century due to the growth of Russian strength in the southern regions and a few Russo-Turkish wars, which partially took place in the Crimean territory. Nevertheless, in 1758 there were around 40,000 slaves captured during a raid on Moldavia and in 1769, during one of the very last Tatar incursions into Russian and Polish territory, the amount of “live booty” was about 20,000 souls.

The demographic importance of the slave trade in the Early Modern Crimea and Ottoman Empire also should not be underestimated. Thousands and thousands of Christian female slaves and children were converted to Islam annually. Soon these neophytes forgot about their non-Turkic origins and their offspring often would not even be aware of their Christian past.”

noot 11: “When this article was already in print, I received a copy of a study by Dariusz Kolodziejczyk, where the author very convincingly suggested that the whole number of slaves taken from Russia and Poland-Lithuania between 1500 and 1700 might roughly be estimated at two million (Dariusz Kolodziejczyk, “Slave Hunting and Slave Redemption as a Business Enterprise: the Northern Black Sea Region in the Sixteenth to Seventeenth Centuries,”

Oriente Moderno n.s. 25:1 (2006): 149-59, esp. 151).”

(SLAVE TRADE IN THE EARLY MODERN CRIMEA FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF CHRISTIAN,MUSLIM, AND JEWISH SOURCES.

MIKHAIL KIZILOV

Oxford University)

Henk Feldmeijer, voorman van de Nederlandse SS (1910-1945) “Op een dag in maart 1944 riep Feldmeijer vijftien a twintig SS’ers bijeen op het bureau van de 4e Afdeling van de Germaanse SS … in Den Haag. … De door Feldmeijer opgeroepen mannen waren over het algemeen arm en nauwelijks opgeleid. Hun gemiddelde leeftijd was laag. … Maar het gezelschap telde ook enkele oudgedienden van de SS, met wie Feldmeijer al langer samenwerkte. … Samen vormden zij een nieuwe, geheime formatie: het Sonderkommando-Feldmeijer. … Het … werd berucht als het nieuwe doodseskader ten behoeve van de Silbertanne-acties, dat alle eerdere moordcommando’s verving. … In totaal rukte het Sonderkommando-Feldmeijer minstens elf keer uit. De acties vonden overal in Nederland plaats, van Breda tot Grootegast en van Beemster tot Velp. Het commando vermoordde 21 burgers. Meestal werden de slachtoffers, net als in de eerste fase van de Aktion Silbertanne, geselecteerd door de Sicherheitsdienst. Maar het was Feldmeijer die vervolgens het Sonderkommando opbelde met het bevel dat een aantal leden zich moest vervoegen bij de betreffende SD-Aussenstellenleiter, die hen verder zou instrueren. Ten minste twee keer heeft Feldmeijer eigenhandig ook het slachtoffer aangewezen. [Anje Lok, uit het Friese Ravenswoud, op 19/20 mei 1944, als vergelding voor de dood van de Landwachter Kees Hartenhof, en pastoor F.J. Schoemaker van de Groningse St. Franciscuskerk, motief onbekend, aanslag mislukte, i.p.v. de pastoor werd kapelaan J.G. Böcker doodgeschoten.(25 sept. 1944).] Het Sonderkommando-Feldmeijer moest een groep professionele en koelbloedige killers worden, maar kon de verwachtingen niet waarmaken. … Een van de Silbertanne-akties waarbij commandoleden steken lieten vallen, vond op 15 aug. 1944 plaats in Noord-Limburg. [De burgemeesters van Asten en Someren werden gedood, maar een derde persoon, Frans Eijsbouts, ontsnapte. Het pistool van schutter Sander Borgers werd door Eijsbouts uit zijn handen geslagen. Het werd later door de politie gevonden. De liquidaties werden daarna steeds vaker door Duitse SD-agenten uitgevoerd, zonder gebruikmaking van het Sonderkommando-Feldmeijer.] Eind augustus kwam er een einde aan de Silbertanne-acties. Hitler had op 30 juli 1944 het [Niedermachungsbefehl] …uitgevaardigd. Volgens dit bevel moesten gearresteerde verzetslieden ter plekke zonder vorm van proces worden doodgeschoten. De afschikkende werking van deze maatregel maakte de omslachtige en risicovolle sluipmoorden overbodig.” [B. Kromhout, De Voorman, Henk Feldmeijer en de Nederlandse SS (Amsterdam/Antwerpen 2012), p. 400 e.v.]

In de oostmuur van de kapel van Guy van Avesnes [in de Domkerk van Utrecht] bevindt zich een spitsboognis, waarin een schildering is aangebracht, die de Kruisiging voorstelt De schildering kwam in 1919 tevoorschijn na de verwijdering van een uit kloostermoppen gemetselde omuur) die haar eeuwenlang beschermd had, zodat zij op twee vierkante gaten van 10 cm zijde na, vrijwel gaaf gebleven is. Blijkens de twee toen gevonden draaipunten in het linkerprofiel van de boog en een afgewerkte aanslag in het overeenkomstig profiel aan de rechterkant was er oorspronkelijk een draaibaar luik voor de schildering bevestigd, zoals er ook nu weer een aanwezig is. De hoogte van de boognis is 1,60 m, de breedte 1,65 m. Onder de nis stond eens een altaar, gewijd aan Sint Margriet, dat het eerst in 1438 vermeld wordt. Op de schildering ziet men in het midden Christus aan het kruis, links Maria, die, ineenzijgend, door Johannes ondersteund wordt, rechts de H. Margaretha met haar attribuut, de draak. De achtergrond is dofrood, de Calvarieberg bruin, het gewaad van Maria, die een witte hoofddoek draagt, blauw met een vaalgroene voering, de mantel van Johannes violet, terwijl Margaretha gehuld is in een roomwitte tunica en een donkere mantel, het monster is vaalgroen van kleur. Uit het hele tafereel en de sterk expressieve gezichten en handen spreekt, ondanks de ingetogen gebaren en houdingen, een fel dramatische aandoening. Ook de dagkanten van de boog zijn beschilderd: men onderscheidt nog vaag de kazuifels en mijters van twee bisschoppen en men ziet St. Barbara, herkenbaar aan de toren, die zij in haar hand draagt. De voorstelling van de Kruisiging is aangebracht op een bruinachtige grondkleur, waaronder op beschadigde plekken geel en rose tevoorschijn komen en waarop men sporen van overschilderingen ziet, bij de Christusfiguur de brede omtrek van een andere figuur, links van Margriet resten van een ander, meer naar links gebogen hoofd. De schildering is niet in temperaverven, maar volgens een voor die tijd nieuw procédé vervaardigd, namelijk met een ongewoon bindmiddel, dat uit caseïne of ei, olie en was bestaat en dat, in afwisselende hoeveelheden gebruikt, tot gevolg heeft gehad, dat er malse dikke partijen en heel dunne lagen naast en door elkaar voorkomen en het koloriet ongewoon vol en fors is. Bijvanck acht het waarschijnlijk, dat de schildering van de hand van de ‘meester van bisschop Zweder van Culemborg’ is, werkzaam ca. 1425 toen hij ook de miniaturen van het missale van Zweder (Bissch. Seminarie te Brixen) vervaardigde. Hoogewerff ziet meer stijlverwantschap met miniaturen uit omstreeks 1430-’40, vooral met die van de ‘meester A.’, onder wiens leiding ca. 1430 te Utrecht twee grote bijbels (respectievelijk in de Koninklijke Bibliotheken van Den Haag en Brussel) verlucht werden en die een Nederlands getijdenboek Stockholm, Kungliga Bibliotek) illustreerde. Positief aan de schilder van de Kruisiging in de Avesneskapel schrijft hij een anoniem paneel toe met een Pietà (collectie Gruter van Linden, Antwerpen) in olieverf. + litteratuur. c.h. de jonge, De ontdekkingen in de Domkerk te Utrecht. Utr. Dagbl, 2 oct. 1919; d.f. slothouwer en c.h. de jonge, Enige vondsten in de Utrechtse Domkerk. bull. oudhk. b. 1929, blz. 150-153; j. por, Drie kruisingstaferelen uit de xve eeuw; oudholland 1937, blz. 26-37; g.j. hoogewerff, De Noordnederlandse schilderkunst (‘s-Gravenhage 1936 vlg) 1, blz. 349-358; a.w. bijvanck, De middeleeuwse boekillustratie in de noordelijke Nederlanden (Antwerpen 1943), blz. 29 en 33.

Rogier van der Weyden, portret van Philippe de Croy, ca. 1460 (gezien Mauritshuis sept. 2017) Philip I de Croÿ (1435–1511) was Seigneur de Croÿ and Count of Porcéan. Philip I was a legitimate heir to the powerful House of Croÿ. He was the eldest surviving son of Antoine de Croy, Comte de Porcéan and Margaret of Lorraine-Vaudémont. Philip was raised with Charles the Bold, who arranged Philip’s marriage to Jacqueline of Luxembourg in 1455. The bride’s father, Louis de Luxembourg, Count of Saint-Pol, was extremely against the alliance and attempted to win his daughter back by force, but the Count of Porcéan closed the borders of Luxembourg and announced that the marriage had been consummated. He was also Governor of Luxembourg and Ligny. Philip had determination and a strong force of personality, and was both respected as an administrator and accomplished in battle. The year after his father died he was titled Knight of the Golden Fleece, and later became Governor of Hainault. He is recorded as a participant in most of the battles of Philip the Good and Charles the Bold, during which his fortunes ranged from being knighted for valour to being held hostage.[1] In 1471 he defected to the King of France with 600 knights but returned to Burgundy to fight for Charles during the Battle of Nancy. It was during the battle that he was taken prisoner. Following Charles’s death, Philip helped arrange the betrothal of his heiress Marie with Emperor Maximilian I. Towards the end of his life, he was employed by the Emperor as Governor of Valenciennes, Lieutenant General of Liege, and Captain General of Hainaut. Philippe commissioned a remarkable church in Château-Porcien, in which he was buried upon his death in 1511. (Wikipedia)

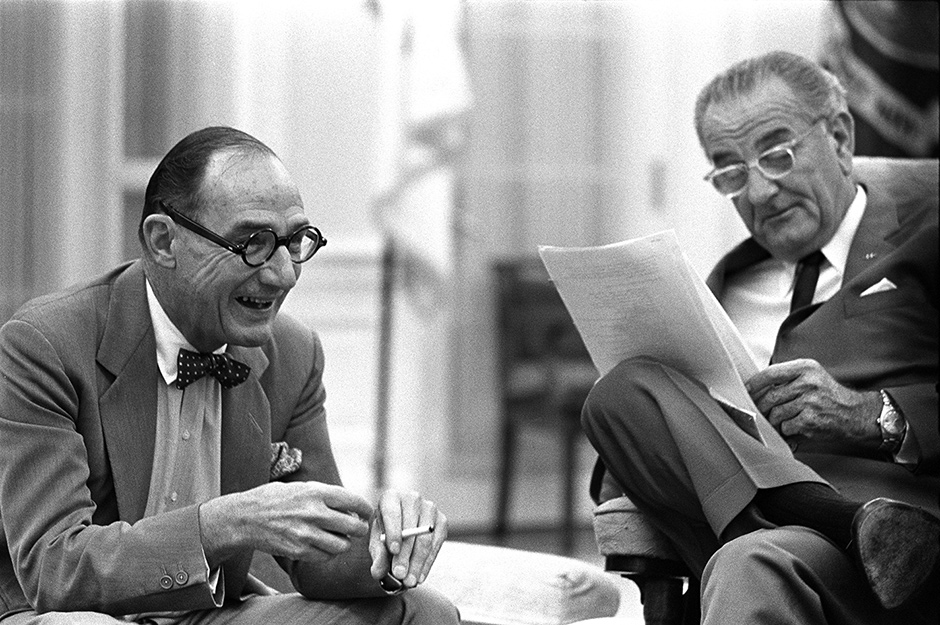

Taped conversation between LBJ and Senate Majority leader Mike Mansfield, June 8, 1965: “LBJ: I don’t exactly see the medium for pulling out [of Vietnam]. … [But] I want to talk to you. … Rusk doesn’t know that I’m thinking this. McNamara doesn’t know I’m thinking this. Bundy doesn’t. I haven’t talked to a human. I’m over here in bed. I just tried to take a nap and get going with my second day, and I couldn’t. I just decided I’d call you. But I think I’ll say to Congress that General Eisenhower thought we ought to go in there and do here what we … did in Greece and Turkey, and … and President Kennedy thought we ought to do this. … But all of my military people tell me … that we cannot do this [with] the commitment [of American forces] we have now. It’s got to be materially increased. And the outcome is not really predictable at the moment. … I would say … that … our seventy-five thousand men are going to be in great danger unless they have seventy-five thousand more … I’m no military man at all. But … if they get a hundred and fifty [thousand Americans], they’ll have to have another hundred and fifty. So, the big question then is: What does Congress want to do about it ? … I think I know what the country wants to do now. But I’m not sure that they want to do that six months from now. … We have … some very bad news on the government [of General Nguyen Cao Ky in Saigon] … Westmoreland says that the offensive that he has anticipated, that he’s been fearful of, is now on. And he wants people as quickly as he can get them. … We seem to have tried everything that we know to do. I stayed here for over a year when they were urging us to bomb before I’d go beyond the line. I have stayed away from [bombing] their industrial targets and their civilian population, although they [the Joint Chiefs] urge you to do it.” (M. Beschloss, Reaching for Glory [New York 2001], p. 345-347)

Wilhelm II, tsaar Nicolaas II, tsarina Alexandra en koningin Victoria. [In the spring of 1914 Nicholas II said to the British Ambassador Sir George Buchanan]: “It was commonly supposed that there was nothing to keep Germany and Russia apart. This was, however, not the case. There was the question of the Dardanelles. Twice in the last two years the Straits had been closed for a short period, with the result that the Russian grain industry had suffered very serious loss. From information which had reached him from a secret source through Vienna he had reason to believe that Germany was aiming at acquiring such a position at Constantinople as would enable her to shut in Russia altogether in the Black Sea. Should she attempt to carry out this policy he would have to resist it with all his power, even should war be the only alternative … though the Emperor said that [he] … wished to live on good terms with Germany … at present the vital necessity was for Russia, France an Britain to unite more closely in order to make it absolutely clear to Berlin that all three entente powers would fight side by side against German aggression.” (D. Lieven, Nicholas II, Emperor of All the Russias [Londen 1993, p. 197)

“Even if, in terms of human loss, the Cultural Revolution was far less murderous than many earlier campaigns, in particular the catastrophe unleashed during Mao’s Great Famine, it left a trail of broken lives and cultural devastation. By all accounts, during the ten years spanning the Cultural Revolution, between 1.5 and 2 million people were killed, but many more lives were ruined through endless denunciations.” (Frank Dikötter, The Cultural Revolution. A people’s history 1962-1976. Londen 2017, p. XVIII)

“The Kimovsk was nearly eight hundred miles away from the Essex [24 okt. 1962] The Yuri Gagarin was more than five hundred miles away. The “high-interest ships” had both turned back the previous day, shortly after receiving an urgent message from Moscow. The mistaken notion that the Soviet ships turned around at the last moment in a tense battle of wills between Khruschev and Kennedy has lingered for decades. [CIA director]McCone erroneously believed that the Kimovsk “turned around when confronted by a Navy vessel” during an “attempted” intercept at 10:35 a.m. Later on, when intelligence analysts established what really happened, the White House failed to correct the historical record. The records of the nonconfrontation are now at the National Archives and the John F. Kennedy Library. The myth of the “eyeball to eyeball” moment persisted because historians of the missile crisis failed to use these records to plot the actual positions of Soviet ships on the morning of Wednesday, October 24.” (M. Dobbs, One Minute To Midnight [2009])

De Maliebaan 35 in de Nederlandse stad Utrecht vormde tijdens de bezetting het hoofdkwartier van de Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB). De Duitse bezetter en daaraan verbonden Nederlandse organisaties namen tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog in meerdere panden aan de Maliebaan hun intrek, waaronder de Duitse Sicherheitsdienst, Luftwaffe, Grüne Polizei, Abwehr en de Nederlandsche SS. Van de NSB nam hun afdeling Propaganda haar intrek op nummer 31, Volkscultuur en Sibbekunde op 33, de Weerbaarheidsafdeling kwam op 76 en de Nederlandse Volksdienst vestigde zich op nummer 90. Maliebaan 35 werd door de NSB gebruikt als hoofdkwartier. Hun leider Anton Mussert had er zijn werkkamer op de eerste verdieping. Het balkon aan de voorzijde van het pand gebruikte hij voor het afnemen van parades op de Maliebaan en voor toespraken. Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler kwam in 1942 naar Nederland en bracht een bezoek aan de Maliebaan 35. (Wikipedia) “de Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging van Anton Mussert had [in 1937] het pand Maliebaan gekocht en als hoofdkwartier in gebruik genomen. … [een statig] pand, met een bescheiden balkon op de eerste verdieping en een enorme tuin aan de achterkant… Aan het eind van 1944 is de Maliebaan niet meer dat machtscentrum van twee, drie jaar eerder. Anton Mussert komt nog maar zelden op zijn oude kantoor. Hij leidt in de laatste oorlogsmaanden een zwervend bestaan.” (A. van Liempt, Aan de Maliebaan [Amsterdam 2015], p. p. 12)

“The insurrection of the gladiators and the devastation of Italy, commonly called the war of Spartacus, began upon this occasion. One Lentulus Batiates trained up a great many gladiators in Capua, most of them Gauls and Thracians, who, not for any fault by them committed, but simply through the cruelty of their master, were kept in confinement for this object of fighting one with another. Two hundred of these formed a plan to escape, but being discovered, those of them who became aware of it in time to anticipate their master, being seventy-eight, got out of a cook’s shop chopping-knives and spits, and made their way through the city, and lighting by the way on several wagons that were carrying gladiators’ arms to another city, they seized upon them and armed themselves. And seizing upon a defensible place, they chose three captains, of whom Spartacus was chief, a Thracian of one of the nomad tribes, and a man not only of high spirit and valiant, but in understanding, also, and in gentleness superior to his condition, and more of a Grecian than the people of his country usually are. When he first came to be sold at Rome, they say a snake coiled itself upon his face as he lay asleep, and his wife, who at this latter time also accompanied him in his flight, his countrywoman, a kind of prophetess, and one of those possessed with the bacchanal frenzy, declared that it was a sign portending great and formidable power to him with no happy event. First, then, routing those that came out of Capua against them, and thus procuring a quantity of proper soldiers’ arms, they gladly threw away their own as barbarous and dishonourable. Afterwards Clodius, the praetor, took the command against them with a body of three thousand men from Rome, and besieged them within a mountain, accessible only by one narrow and difficult passage, which Clodius kept guarded, encompassed on all other sides with steep and slippery precipices. Upon the top, however, grew a great many wild vines, and cutting down as many of their boughs as they had need of, they twisted them into strong ladders long enough to reach from thence to the bottom, by which, without any danger, they got down all but one, who stayed there to throw them down their arms, and after this succeeded in saving himself. The Romans were ignorant of all this, and, therefore, coming upon them in the rear, they assaulted them unawares and took their camp. Several, also, of the shepherds and herdsmen that were there, stout and nimble fellows, revolted over to them, to some of whom they gave complete arms, and made use of others as scouts and light-armed soldiers. Publius Varinus, the praetor, was now sent against them, whose lieutenant, Furius, with two thousand men, they fought and routed. Then Cossinius was sent with considerable forces, to give his assistance and advice, and him Spartacus missed but very little of capturing in person, as he was bathing at Salinae; for he with great difficulty made his escape, while Spartacus possessed himself of his baggage, and following the chase with a great slaughter, stormed his camp and took it, where Cossinius himself was slain. After many successful skirmishes with the praetor himself, in one of which he took his lictors and his own horse, he began to be great and terrible; but wisely considering that he was not to expect to match the force of the empire, he marched his army towards the Alps, intending, when he had passed them, that every man should go to his own home, some to Thrace, some to Gaul. But they, grown confident in their numbers, and puffed up with their success, would give no obedience to him, but went about and ravaged Italy; so that now the senate was not only moved at the indignity and baseness, both of the enemy and of the insurrection, but, looking upon it as a matter of alarm and of dangerous consequence, sent out both the consuls to it, as to a great and difficult enterprise. The consul Gellius, falling suddenly upon a party of Germans, who through contempt, and confidence had straggled from Spartacus, cut them all to pieces. But when Lentulus with a large army besieged Spartacus, he sallied out upon him, and, joining battle, defeated his chief officers, and captured all his baggage. As he made toward the Alps, Cassius, who was praetor of that part of Gaul that lies about the Po, met him with ten thousand men, but being overcome in the battle, he had much ado to escape himself, with the loss of a great many of his men. When the senate understood this, they were displeased at the consuls, and ordering them to meddle no further, they appointed Crassus general of the war, and a great many of the nobility went volunteers with him, partly out of friendship, and partly to get honour. He stayed himself on the borders of Picenum, expecting Spartacus would come that way, and sent his lieutenant, Mummius, with two legions, to wheel about and observe the enemy’s motions, but upon no account to engage or skirmish. But he, upon the first opportunity, joined battle, and was routed, having a great many of his men slain, and a great many only saving their lives with the loss of their arms. Crassus rebuked Mummius severely, and arming the soldiers again, he made them find sureties for their arms, that they would part with them no more, and five hundred that were the beginners of the flight he divided into fifty tens, and one of each was to die by lot, thus reviving the ancient Roman punishment of decimation, where ignominy is added to the penalty of death, with a variety of appalling and terrible circumstances, presented before the eyes of the whole army, assembled as spectators. When he had thus reclaimed his men, he led them against the enemy; but Spartacus retreated through Lucania toward the sea, and in the straits meeting with some Cilician pirate ships, he had thoughts of attempting Sicily, where, by landing two thousand men, he hoped to new kindle the war of the slaves, which was but lately extinguished, and seemed to need but little fuel to set it burning again. But after the pirates had struck a bargain with him, and received his earnest they deceived him and sailed away. He thereupon retired again from the sea, and established his army in the peninsula of Rhegium; there Crassus came upon him, and considering the nature of the place, which of itself suggested the undertaking, he set to work to build a wall across the isthmus; thus keeping his soldiers at once from idleness and his foes from forage. This great and difficult work he perfected in a space of time short beyond all expectation, making a ditch from one sea to the other, over the neck of land, three hundred furlongs long, fifteen feet broad, and as much in depth, and above it built a wonderfully high and strong wall. All which Spartacus at first slighted and despised, but when provisions began to fail, and on his proposing to pass further, he found he was walled in, and no more was to be had in the peninsula, taking the opportunity of a snowy, stormy night, he filled up part of the ditch with earth and boughs of trees, and so passed the third part of his army over. Crassus was afraid lest he should march directly to Rome, but was soon eased of that fear when he saw many of his men break out in a mutiny and quit him, and encamped by themselves upon the Lucanian lake. This lake they say changes at intervals of time, and is sometimes sweet, and sometimes so salt that it cannot be drunk. Crassus falling upon these beat them from the lake, but he could not pursue the slaughter, because of Spartacus suddenly coming up and checking the flight. Now he began to repent that he had previously written to the senate to call Lucullus out of Thrace, and Pompey out of Spain; so that he did all he could to finish the war before they came, knowing that the honour of the action would redound to him that came to his assistance. Resolving, therefore, first to set upon those that had mutinied and encamped apart, whom Caius Cannicius and Castus commanded, he sent six thousand men before to secure a little eminence, and to do it as privately as possible, which that they might do they covered their helmets, but being discovered by two women that were sacrificing for the enemy, they had been in great hazard, had not Crassus immediately appeared, and engaged in a battle which proved a most bloody one. Of twelve thousand three hundred whom he killed, two only were found wounded in their backs, the rest all having died standing in their ranks and fighting bravely. Spartacus, after this discomfiture, retired to the mountains of Petelia, but Quintius, one of Crassus’s officers, and Scrofa, the quaestor, pursued and overtook him. But when Spartacus rallied and faced them, they were utterly routed and fled, and had much ado to carry off their quaestor, who was wounded. This success, however, ruined Spartacus, because it encouraged the slaves, who now disdained any longer to avoid fighting, or to obey their officers, but as they were upon the march, they came to them with their swords in their hands, and compelled them to lead them back again through Lucania, against the Romans, the very thing which Crassus was eager for. For news was already brought that Pompey was at hand; and people began to talk openly that the honour of this war was reserved to him, who would come and at once oblige the enemy to fight and put an end to the war. Crassus, therefore, eager to fight a decisive battle, encamped very near the enemy, and began to make lines of circumvallation; but the slaves made a sally and attacked the pioneers. As fresh supplies came in on either side, Spartacus, seeing there was no avoiding it, set all his army in array, and when his horse was brought him, he drew out his sword and killed him, saying, if he got the day he should have a great many better horses of the enemies’, and if he lost it he should have no need of this. And so making directly towards Crassus himself, through the midst of arms and wounds, he missed him, but slew two centurions that fell upon him together. At last being deserted by those that were about him, he himself stood his ground, and, surrounded by the enemy, bravely defending himself, was cut in pieces.” (Plutarchus, Leven van Crassus)

24 June 1859: Battle of Solferino (south of Lake Garda in Lombardy, Italy) “For fifteen hours on 24 June, 107,000 French and 44,000 Piedmontese troops fought a battle against 151,000 Austrians along a twelve mile front … After fierce fighting and heavy losses, the French finally stormed the key point, the Cypress Hill. By 2 p.m. a French regiment had captured the heights of Solferino … [Emperor Napoleon III of France] then turned his attention to the last Austrian stronghold at Cavriana … At 3 p.m. the Austrian centre broke, and [the Austrian emperor] Franz Joseph ordered a general retreat. As he rode off to Goito the hot weather … ended in a tremendous thunderstorm with heavy rain, which put a stop to all operations in the battlefield, as it was to dark for the troops to see anything. When the sky cleared an houtr later, the French found that the Austrians had gone. The losses on both sides were very heavy [French killed, wounded and missing: abt. 12.000, Piedmontese: 5500, Austrians: abt. 22.000] … The Austrians had withdrawn into the ‘Quadrilateral’ – the formidabel defensive works based on Mantua, Peschiera, Verona and Legnano … As the Piedmontese army began to invest Peschiera, the world waited for a third and even bloodier battle than Magenta and Solferino. Then. to the surprise of his generals, soldiers, allies and enemies, … [Napoleon III] offered the Austrians an armistice till 15 August, and proposed that he and Franz Joseph should meet to discuss peace terms. The Austrians agreed … There was much speculation at the time – and it has continued ever since – about the reason which induced Napoleon III to make peace with Austria after Solferino. He seems to have been influenced by four factors [: 1. he realized that the French would suffer even greater losses than at Solferino when they tried to storm the defences of the Quadrilateral, 2. he resented the attitude of the Piedmontese and he felt that [Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia ]Cavour’s plan was for the French to do most of the fighting and for Piedmont-Sardinia to reap most of the advantages, 3. he was worried that a prolongation of the war would eventually lead to a general European war (there was as yet no sign of Britain or Russia abandoning there neutrality, but there was a possibility that the German Diet would agree to sending an army corps to the Upper Rhine), 4. he was alarmed at the spread of revolution in Italy (Tuscany, Parma, Modena, Lucca, and the Papal province of the Romagna), and conscious of the difficulties in which this (especially of course a revolution in the Papal States) would involve him with the clergy in France. Also disturbing was the arrival of Hungarian revolutionary Kossuth in Genoa, who was obviously trying to incite a revolution in Hungary. A few months later Napoleon wrote to the Austrian Ambassador: “I was disgusted to have the Revolution following my heels, and Kossuth and [Hungarian general] Klapka as allies; I would be seen as the leader of all the scum of Europe”.] (J. Ridley, Napoleon III and Eugenie [London 1979], p. 450-454)

“The images painted and drawn on the walls [at Peche Merle, France] and at other Upper Palaeolithic sites in Europe show clear evidence of conceptual, abstract thought – the earliest such evidence in the world. The extraordinarily detailed artwork at Chauvet cave has been dated to around 32,000 years ago, the oldest in France. Recently discovered drawings at Fumane cave, near Verona in northern Italy, may date from as early as 35,000 years ago, which would make them them the oldest examples of cave art anywhere in the world. … The inhabitants of these European caves were clearly talented artists, and their culture marks a distinct departure from that of the Neanderthals that preceded them. It marks the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe, and broadcasts the arrival of fully modern humans on the scene. … We saw earlier that the most obvious location from which to enter Europe, the Middle East, appears to have contributed little to the gene pool of Europeans. The Y-chromosome lineage defined solely by [the M89 marker], which would have characterized the earliest Middle Eastern populations around 45,000 years ago, is simply not very common in western Europe. It is such a tiny hop across the Bosporus from the Middle East to Europe that we might ask why it took so long – perhaps 10,000 years – for modern humans to make a significant foray into western Europe. … [The M173 marker] is found at high frequency throughout western Europe. Intriguingly, the highest frequencies are found in the far west, in Spain and Ireland, where M173 is present in over 90 per cent of men. It is, then, the dominant marker in western Europe, since most men belong to the lineage that it defines. … the most likely date for the origin of M173 is around 30,000 years ago. This date means that the man who gave rise to the vast majority of western Europeans lived around 30,000 years ago – consistent with a recent African diaspora, and again showing that Neanderthals could not have been direct ancestors of modern Europeans. Significantly, it is around this time that the Upper Palaeolithic becomes firmly established in Europe – and the Neanderthals disappear. … By 25,000 years ago they had disappeared entirely. [How and why this happened is still not definitely established. It is very unlikely however, that the Cro Magnons exterminated the Neanderthals physically. There is simply, as of now, no archelogical proof for that.] … Whatever the causes of their demise, Neanderthals had given up the ghost within a few thousand years of the arrival of modern humans. After 30,000 years, the only remains found in Europe are those of fully modern humans – often called Cro-Magnons … These early Europeans were much more gracile, and significantly taller, than their Neanderthal neighbours [often 180 cm, to Neanderthals around 165 cm], … with long limbs.” (Spencer Wells, The Journey of Man, Princeton/Oxford 2002, p. 126 et seq.)

What was the Temple of Solomon? According to the Bible, it was the Israelites’ first permanent ‘house’ of God, built specifically to house the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark, a gold covered wooden chest containing the Ten Commandments, had originally been carried by the chosen people and Moses through the desert. When they arrived at the promised land of Canaan, they kept the Ark at the heart of the tabernacle, a tent-like structure regarded as God’s dwelling place on Earth. After King Saul unified the Israelites, they settled in Jerusalem under his successor David. It was David’s son Solomon who built the luxurious temple, now known as the Temple of Solomon. Eventually it would become the Israelites’ only legitimate place of worship. In Jewish history this time is known as the First Temple period, and begins at around 1,000BC. What evidence is there that the Temple of Solomon existed? The only evidence is the Bible. There are no other records describing it, and to date there has been no archaeological evidence of the Temple at all. What’s more, other archaeological sites associated with King Solomon – palaces, fortresses and walled cities that seemed to match places and cities from the Bible – are also now in doubt. There is a growing sense among scholars that most of these archaeological sites are actually later than previously believed. Some now believe there may be little or no archaeological evidence of King Solomon’s time at all, and doubt that he ruled the vast empire which is described in the Bible. Why did the appearance of the stone tablet, the Jehoash inscription, cause such a sensation? Inscriptions from the First Temple Period are extremely rare. In fact only one other royal inscription from this period has been found in Israel. The ‘House of David’ Victory Stele, now in the Israel Museum, contains the only reference to Solomon’s father David which exists outside the Bible. The Jehoash inscription appeared to be of even greater importance, offering the only known archaeological evidence for Solomon’s most celebrated building. It also seemed to corroborate some verses in the Bible which mentioned the Temple. The description of repairs to the Temple carried out by King Jehoash corresponds closely to Kings 2 Chapter 12. This gave the Inscription potentially enormous significance. Why did the authorities set up an inquiry? Although the Geological Survey of Israel concluded that the Jehoash Inscription was genuine, there were a number of issues that worried archaeologists, philologists and the police. The lack of any authenticated provenance was a major problem. No one could demonstrate where the inscription had been found, and for reputable museums that raised significant doubts. Moreover, some scholars were raising questions about the language of the inscription. Was it consistent with the Hebrew of the First Temple Period? For the police it was a matter of law. Under Israeli law any ancient artefact discovered after 1978 belongs to the state. So if this stone was genuine and had been recently unearthed, then its sale was illegal. And if it was after all a fake, then the police wanted to find out how and where it had been produced. Also causing concern was the discovery of a link between the inscription and another Biblical antiquity which had surfaced in Israel and enjoyed similar acclaim. This artefact was hailed as the ossuary – or bone box – of Jesus’ brother. Its ancient Aramaic inscription read, ‘James, Son of Joseph, Brother of Jesus’, and caused a similar worldwide sensation. It was displayed for the general public in Canada, in the Royal Ontario Museum and the exhibit received almost half a million visitors. Intriguingly, its owner was the same man who was handling the Jehoash Inscription. This coincidence prompted the Israel Antiquities Authority to set up an inquiry to examine both artefacts. How did the discovery of marine fossils in the patina finally prove that the stone and the ossuary were fakes? The patina is a layer on ancient stone which builds up over time as the stone reacts chemically with the soil, air or water it touches. An object which has been buried, as the Jehoash Inscription was said to be, will form a patina with the chemical signature of the soil around it. In the Judean hills around Jerusalem, the limestone in the rocks will produce a patina composed mainly of calcite (calcium carbonate). Although chemically the patina on the Jehoash inscription and the ossuary corresponded very closely to a natural patina from Jerusalem, investigators were astonished to discover that in both cases it contained microfossils of marine organisms called foraminifera. These occur naturally in chalk, a calcium carbonate rock which is produced at the bottom of the sea, but these fossils do not dissolve in water and so cannot occur in a calcium carbonate patina. It was clear to investigators that the patina must be an artificial chemical mix in which chalk had been ground up to produce the required calcium carbonate. The marine fossils were a clear indication of the technique the forgers had used. Why did investigators conclude that the stone probably came from a crusader castle? Royal monumental inscriptions were sometimes written on black, rectangular-shaped, basalt stone. The forgers clearly knew this and chose a stone which was black. But mineralogical tests showed they had made a mistake. The tablet was not basalt but the unusual stone greywacke. This type of stone is not native to Israel, and would certainly not have been found in Judah (modern Jerusalem) during the reign of King Jehoash. In fact, the closest source for the low grade metamorphic greywacke used for the tablet is western Cyprus. Assuming the forgers would not have gone so far afield to obtain a stone tablet, investigators concluded that this Cypriot stone must have been found locally. But why would a stone from Cyprus have been found in Israel? There seemed one obvious possibility. During the Crusades stones were used as ballast on ships. They were frequently collected from one Crusader port, including Cyprus, and used by them for construction elsewhere. The Fortress of Apollonia, only 15 kilometres up the coast from Tel Aviv, was built by the Crusaders and part of it still stands today. It contains all sorts of exotic rectangular stones – including greywacke. It seems very probable that the forgers took one of these stones, or one from another Crusader building, knowing it to be old and weathered, and already cut to a rectangular shape. It was also the right colour, and they may never have realised their error: that the stone they had chosen would not have been found in Israel in Biblical times. What effect has the discovery of this elaborate fake had on the world of archaeology? Police now suspect that artefacts produced by the same team of forgers may have reached collections and museums all over the world. The same investigators have found many other objects to be fakes. Some Israeli archaeologists are concerned that the whole archaeological record has been seriously contaminated and distorted by the forgers’ activities. They are now suggesting that everything which came on to the antiquities market in Israel in the last 20 years without a clear and unambiguous provenance should be considered a fake unless proven otherwise. (www.bbc.co)

Count Karl Ferdinand von Buol, Austrian Minister of Foreign Affairs 1852-1859: In Febr. 1853 Tsar Nicholas I demanded a Russian protectorate over all 12 million Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire, with control of the Orthodox Church’s hierarchy. The Sultan accepted some, but rejected the more sweeping demands. Russia reacted with an invasion across the Pruth River into the Ottoman-controlled Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. ” … the immediate problem to be solved was the Russian military presence in the principalities. Nicholas had ordered the move to put pressure on Turkey to agree to the terms dictated by Menshikov, but the invasion had also disrupted the regional strategic balance. The Austrians were displeased by the deployment because any conflict in the area would disrupt trade along the Danube, the main conduit into Europe. In theory Austria was Russia’s ally and Nicholas took Vienna’s support for granted, but the Austrians were now suspicious of Russian territorial intentions in the Balkans. Even so, they were in a difficult position. If they threw in their lot with Britain and France their proximity to Russia would force their army to bear the brunt of the fighting. Yet, full-blooded support for Nicholas would only make them more dependent on Russia. There was also the question of national pride. Four years earlier the Austrians had been forced to ask for Russian help in quelling an uprising by Magyar nationalists and there was a lingering sense of shame and resentment. Nicholas had forgotten the old dictum that personal indebtedness can often spoil the closest of friendships. And so it proved. When Britain and France put pressure on the Austrians to involve themselves in the crisis they were happy to make hasty arrangements for a governmental meeting in Vienna. Convened by … Count Buol-Schauenstein … the meeting had the twin aims of ending the Russian occupation of the principalities and of settling the dispute over the protection of the Orthodox Christian communities within the Ottoman Empire.” (T. Royle, Crimea. The Great Crimean War 1854-1856, p. 65 et seq.)

Het totaal aantal joodse sovjetburgers dat in de eerste vijf maanden van de veldtocht [in de Sovjet-Unie, juli-nov. 1941] slachtoffer werd van Einsatzgruppen, oversteeg een half miljoen.” Reichsführer SS Himmler had op 31 juli 1941 bevolen: “alle joden moeten worden doodgeschoten. Vrouwen moet men in het moeras drijven.” Vanaf half augustus verlegden de Einsatzgruppen hun grenzen. Wat was begonnen als het executeren van joodse mannen in de weerbare leeftijd en later ook van vrouwen, werd een politiek van zonder onderscheid elimineren van de joodse bevolking in de bezette gebieden, inclusief kinderen. (G. Knopp, Hitlers Holocaust [2000], p. 71-72)

september 1939 gearresteerd of gevangengenomen werden en in drie verschillende kampen werden vastgehouden. Een ervan was in het bos van Katyn. … Koelik, de bevelhebber van het Poolse front, stelde voor om alle Polen vrij te laten. Vorosjilov was het hier mee eens, maar Mechlis dacht dat er zich vijanden onder hen bevonden. Stalin hield de vrijlating tegen, maar Koelik bleef volhouden. Stalin stelde een compromis voor. De Polen werden vrijgelaten – behalve 26.000 officieren over wie het Politbureau uiteindelijk op 5 maart 1940 zou beslissen. … [Beria rapporteerde] plichtsgetrouw … dat 14.700 officieren, landeigenaren en politiemannen en 11.000 ‘contra-revolutionaire’ landeigenaren, ‘spionnen en saboteurs … vijanden van de sovjet-macht’ berecht zouden moeten worden. … Stalin krabbelde er als eerste zijn handtekening onder … Het bloedbad was een flinke hoeveelheid ‘besmet werk’ voor de NKVD, die gewend was aan de doodstraf van enkele slachtoffers per keer, maar er was een man die deze taak aankon. [De tsjekist] Blochin reisde naar het kamp Ostatsjkov, waar hij en twee andere tsjekisten een barak in orde maakten, voorzagen van geluidsdichte muren en besloten om 250 executies per nacht uit te voeren. Hij bracht een slagersschort en -pet mee die hij opzette, terwijl hij begon aan een van de grootste massamoorden die ooit door een enkel individu gepleegd is: in precies 28 dagen doodde hij 7000 mensen, waarbij hij een Duits Waltherpistool gebruikte om toekomstige ontmaskering te voorkomen. De lijken werden op verschillende plekken begraven – maar de 4500 uit het kamp bij Kozelsk werden in het bos van Katyn begraven.” (S. Sebag Montefiore, Stalin. Het hof van de rode tsaar [Utrecht 2004], p. 316-317)

Budionny’s Konarmia. “[By late June/early July 1920] Budionny’s spectacular advance had begun to run out of steam. His greatest assets – speed and mystique – had been eroded by the need to slow down and fight. After the initial reactions of panic and desertion, the Polish troops facing him had steadied and become battle-hardened. … This was not what Budionny and his men had anticipated when they began their invasion of Poland. They had been told that they were being sent to liberate the Ukrainian and Polish workers from the ‘Polish Lords’, and had expected to be received as heroes. They had also been led to believe that they would be marching through a land rich in the luxuries of ‘bourgeois’ life. In the event, they found themselves having to fight every inch of the way against determined troops who were self-evidently not all ‘Polish Lords’. Their march took them through poverty-stricken countryside ravaged by years of war, dotted with villages made up squalid hovels and ramshackle towns populated mainly by Jews. While some of the younger peasants and Jews welcomed and even joined them, most viewed them with puzzled apprehension. … As well as killing obvious ‘enemies of the people’, such as priests and landowners, [the Red soldiers] also raped and murdered civilians at random. Their officers insisted that they treat the Jews with forbearance, but once night fell, there was no stopping the rapine. They also massacred prisoners of war, often just for their boots or their uniforms. They were depressed and morale was not good, and they were also sick. Many suffered from dysentery and, according to the writer Isaac Babel … every single one of them had syphilis.” (A. Zamoyski, Warsaw 1920, Lenin’s failed conquest of Europe [2008] p. 59-60)

Generaal Maxime Weygand. “[After the fall of Wilno on 12 July 1920, a] new [Polish] Government of National Defence was formed under the Peasant leader Wincenty Witos … The new government also issued an appeal for help to the Entente. Neither Britain nor France wished to get involved, but they felt they had to do something, so they took two steps, neither of which was to have any influence on the course of events. The first was a telegram to Moscow despatched by the British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon, suggesting a ceasefire along a ‘minimum Polish frontier’sketched by himself and a peace conference in London [the Curzon Line]. The Russian response was predictable. Chicherin questioned the right of Entente, which was still waging war on Soviet Russia through the agency of the Whites, to mediate a peace. … At the same time, the Franco-British response demonstrated that the Entente was unwilling to come to Poland’s aid directly. Lenin calculated that it was therefore safe to continue the offensive, while agreeing to direct talks with Poland. … The other measure taken by the Entente was to send an Inter-Allied Mission to Warsaw … Much of their energy was directed at trying to place [French general Maxime] Weygand in command of the Polish army.” (Zamoyski, Warsaw 1920, Lenin’s failed conquest of Europe [2008] p. 57-58)

M.I. Tukhachevsky, “the Red Napoleon”, Red Army KomZapFront, or commander of the Western (Polish) front 1920-1921 (sitting, far left). Behind him S.M. Budionny, commander of the 1st Cavalry Army (Konarmia I) and to his right (sitting in the middle) K.E. Voroshilov, Budionny’s political commissar, a close associate of Stalin, who was commissar to the South-Western front. By the spring of 1920 the Konarmia consisted of 4 divisions of horse, a brigade of infantry, 52 field guns and countless tachankas (tachanka: a heavy machine-gun mounted on the back of a horse-drawn open buggy, with one man driving the horses and two manning the gun). It also had 5 armoured trains and 8 armoured cars (and also a squadron of 15 planes, most of which were captured however by a Polish raid). (Zamoyski, Warsaw 1920, Lenin’s failed conquest of Europe [2008] p. 42 et seq.)

Jozef Pilsudski. “He was born in 1867 into the minor nobility and brought up in the cult of Polish patriotism. In his youth he embraced socialism, seeing in it the only force that could challenge the Tsarist regime and promote the cause of Polish independence. [… he had, at the age of nineteen, supplied Lenin’s elder brother with the explosives for the bomb which he had hurled at Tsar Alexander III.]His early life reads like a novel, with time in Russian and German gaols punctuating his activities as polemicist, publisher of clandestine newspapers, political agitator, bank-robber, terrorist and urban guerilla leader. In 1904 Pilsudski put aside political agitation in favour of para-military organization. He organized his followers into fighting cells that could take on small units of Russian troops or police. A couple of years later, in anticipation of the coming war, he set up a number of supposedly sporting associations in the Austrian partition of Poland which soon grew into an embryonic army. On the eve of the Great War Austro-Hungary recognized this as a Polish Legion, with the status of irregular auxiliaries fighting under their own flag, and in August 1914 Pilsudski was able to march into Russian-occupied territory and symbolically reclaim it in the name of Poland. He fought alongside the Austrians against Russia for the next couple of years, taking care to underline that he was fighting for Poland, not for the Central Powers. In 1916 the Germans attempted to enlist the support of the Poles by creating a kingdom of Poland out of some of the Polish lands, promising to extend it and give it full independence after the war. They persuaded the Austrians to transfer the Legion’s effectives, which had grown to some 20,000 men, into a new Polish army under German command … Pilsudski, who had been seeking an opportunity to disassociate himself from the Austor-German camp in order to have his hands free when the war ended, refused to swear the required oath of brotherhood with the German army, and was promptly interned in the fortress of Magdeburg. His legion was disbanded, with only a handful joining the [Polish army under German command] and the rest going into hiding. … Pilsudski was set free at the outbreak of revolution in Germany and arrived in Warsaw 11 November 1918, the day the armistice was signed in the west. … Piludski felt that thirty years spent in the service of his enslaved motherland gave him an indisputable right to leadership. His immense popularity in Poland seemed to endorse this. But that was not the view of the victorious Allies in the west, nor of the Polish National Committee, waiting in Paris to assume power in Poland. After some negotiation a deal was struck, whereby the … pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski … who … was trusted by the leaders of [Britian, France and the USA], came from Paris to take over as Prime Minister, with Pilsudski remaining titular head of state and commander-in-chief. … While the Poles were being publicly urged by Lloyd George and Clemenceau to make peace [with the Bolsheviks], they were receiving conflicting messages from other members of the British government and from the French general staff … This suited Pilsudski, who continued to consilidate his own military position. On 3 January [1920] he captured the city of Dunaburg (Daugavpils) from the Russians and handed it over to the Latvians … thereby cutting Lithuania off from Russia. … Lenin was not interested in peace either. He mistrusted the Entente, which he believed to be dedicated to the destruction of the Bolshevik regime in Russia. He saw Pilsudski as their tool, and was determined to ‘do him in’ sooner or later. He feared a Polish advance into Ukraine, where nationalist forces threatened Bolshevik rule, and was convinced the Poles were contemplating a march on Moscow. Russia was isolated and the Bolsheviks’grip on power fragile. At the same time, the best way of mobilizing support was war, which might also allow Russia to break out of isolation and could yield some political dividends. … In the final months of 1919 Lenin increased the number of divisions facing Poland from five to twenty, and in January 1920 the Red Army staff’s chief of operations … produced his plan for an attack on Poland, scheduled provisionally for April. This was accepted by the Politburo on 27 January, although … Trotsky and … Chicherin warned against launching an unprovoked offensive. … Two weeks later, on 14 February, Lenin took the final decision to attack Poland, and five days after that the Western front command was created. … Operations, originally scheduled to begin in April, were delayed [however] by the need to disengage units from the fight against the remnants of Denikin’s [White] forces in the Caucasus and transfer them to the Polish theatre. This gave the Poles a chance. … On 25 April [1920] one Ukrainian and nine Polish divisions under the direct command of Pilsudski launched an offensive against the Russian South-Western Front in Ukraine … In just under two weeks [the Poles] had defeated two Soviet army groups, taken over 30,000 prisoners, captured huge quantities of materiel, moved the front forward by some two hundred kilometres and occupied [Kiev] the strategically and politically important capital of Ukraine. … But Pilsudski admitted to feeling uneasy. The operation had failed in its purpose. He had damaged the two Russian armies, but they had saved themselves by flight, and could be operational once more as soon as their losses had been made up. … [But this was nothing compared] to the blunder he had committed in diplomatic terms … [To the outside world the Polish offensive appeared as an unprovoked invasion of Russia. In early May 1920 a communist ‘Hands off Russia’committee in England] called for a boycott, the consequence of which was that dockers in the port of London refused to load a shipment of arms bound for Danzig … Large sections of world opinion swung against [Poland], and the Entente distanced itself. … Lloyd George was incensed, and even anti-Bolsheviks such as Churchill were annoyed that [Pilsudski] had struck now and not in the previous year, when he could have saved Denikin.” ” (A. Zamoyski, Warsaw 1920, Lenin’s failed conquest of Europe [2008], p. 4-38)

Sir Edward Grey. British Foreign Secretary 1905-1916. “The repercussions of the assassination at Sarajevo intruded into Anglo-Russian relations only slowly. During the July crisis [1914], Grey had followed the policy of close collaboration with Germany that had worked so successfully during the first Balkan crisis. It was not until 24 July, when Buchanan informed Grey of Russia’s hope that Britain would ‘express strong reprobration’ at Austria-Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia, that much thought seems to have been given to Russia outside of the negotiations about Persia. … the foreign secretary remained largely aloof from his advisers at the Foreign Office and the issue of war or peace was decided in the Cabinet. There was some reflection of them, however, when Grey made his dramatic speech in the House of Commons on 3 August [1914], at which time the foreign secretary briefly alluded to the fact that if Britain remained neutral in the war the ententes with France and Russia would be at an end, regardless of the outcome of hostilities. The impact of Russia in that venue and on the British decision to go to war is a contentious point. On the one hand, Keith Wilson [The Policy of the Entente (Cambridge, 1985)] argues that Britain went to war to protect her interests in Asia from the consequences of standing aloof from the war – in short that the maintenance of good Anglo-Russian relations was the determining factor in Grey’s advocacy of war. On the other hand Zara Steiner [Britain and the origins of the First World War (London, 1977)] believes that Grey attempted to pursue an even-handed policy, but in the final analysis was pushed by German actions into siding with the entente. Looked at from the perspective of Anglo-Russian relations in the period from 1894 to 1914, there can be no doubt that Steiner’s argument is correct. … Grey’s willingness to renegotiate the Anglo-Russian Convention [of 1907] in 1914 was not a sign that the foreign secretary was aiming at some sort of Anglo-Russian alliance. Rather, it was an admission that the patch placed in 1907 on the long-standing running sore of Anglo-Russian enmity was only temporary.” (K. Neilson, The British and the last Tsar. British policy and Russia, 1894-1917 [New York 1995], p. 339-340)

Lord Lansdowne. British Foreign Secretary 1900-1905. “The Russo-Japanese War had a profound effect on Anglo-Russian relations. Russia’s defeat brought to an end a decade of Anglo-Russian quarrels in China and the Far East. The defeat of the Russian Navy [Tsushima 27-28 May 1905] had eliminated one of the components of the two-power standard. And Russia’s military setbacks meant that threats to India, while they were still likely to occur, had less force. Although Kitchener continued to trumpet the Russian threat, all agreed that this was now a threat for the future and most accepted as a fact that at present the ‘defence of India lies mainly with the [Foreign Office]…’. Indeed the Foreign Office had already aided in the defence of India via the provisions of the renewed Anglo-Japanese alliance. Further, all this had been achieved without Britain’s becoming completely estranged from Russia, offering the possibility of a postwar improvement in relations between the two countries. It was also a vindication of Lansdowne’s diplomacy. Both the Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Anglo-French entente had demonstrated that they could survive a major international crisis. … The Anglo-French entente had not stood in the way of the Franco-Russian Dual Alliance, and Britain’s support for the French over Morocco must have seemed doubly valuable to Paris in the light of Russia’s weakened condition and frequent flirtations with Germany. … In the autumn of 1905, the British position was dramatically improved from that of two years before.”(K. Neilson, The British and the last Tsar. British policy and Russia, 1894-1917 [New York 1995], p. 264)

Tsaar Nicolaas II en koning George V “The problems of evaluation were never more obvious than with respect to Nicholas II. Quite rightfully, the British noted that ‘[t]he Emperor is the all important factor in foreign policy’. But they were never able to come to grips with the personality of the elusive monarch. In such circumstances, wishful thinking could take over. Since close Anglo-Russian relations were desired, the best possible interpretation was put on Nicholas’s every utterance and action. Perhaps unconsciously sharing the traditional view of the Russian peasantry that all ills could be attributed tot the Tsar’s officials rather than to the monarch himself, the British tended to view Nicholas as influenced by the last person who advised him. * This allowed them to ignore the fact that Nicholas very much ran his own ship, something that the peace negotiations in the Russo-Japanese War [1904-1905] underlined. It was not until during the First World War that Robert Bruce Lockhart, the acting British consul in Moscow, got closer to the truth : ’the Emperor is by no means stupid, talks well and to the point, and is fully aware of what he is doing … he is obstinate and vindictive, and quite obsessed with the idea that autocracy is his and his children’s by Divine right’. [Lockhart to Grey, disp.2, 22 Jan. 1916]. But to have accepted this view would have ran counter to the British belief – hope may be more accurate – in Nicholas II as a closet liberal. Nicholas’s evident disregard for the Duma, a body which for the British was the touchstone of a favourable future for Russia, was largely ignored or blamed on the machinations of his advisors. The required Nicholas became the accepted one.” (K. Neilson, The British and the last Tsar. British policy and Russia, 1894-1917 [New York 1995], p. 83) * In June 1905 Hardinge argued, that the person who saws Nicholas last ‘is likely to have the most influence upon him’. (idem, p. 56)

Jean-Leon Gerome, Slave market in Northern Africa. “Although all these slave counts fluctuated in the short term, there are enough and they are consistent enough over the long run to produce a workable total for the slave populations in Barbary for the century 1580-1680 … Even when keeping to the lower estimates … the averages soon add up: around 27.000 in Algiers and its dependencies, 6.000 in Tunis, and perhaps 2.000 in Tripoli and the smaller centers combined. … The figure of 35.000 that we have arrived at here can be taken as an averaged-out white slave count for Barbary, roughly how many captives were held at any given time between 1580 and 1680. … The result, then, is that between 1530 and 1780 there were almost certainly a million and quite possibly as many as a million and a quarter white, European Christians enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast. … the estimates arrived at here make it clear that for most of the first two centuries of the modern era, nearly as many Europeans were taken forcibly to Barbary and worked or sold as slaves as were West Africans hauled off to labor on plantations in the Americas. … Hardest hit in [the raids of the Barbary corsairs] … were the sailors, merchants, and coastal villagers of Italy and Greece and of Mediterranean Spain and France. … Overall, relatively few Christian females ended up enslaved in Barbary – some estimates place their proportion as low as 5 percent among the generality of European slaves there.” ( R.C. Davis, Christian slaves, Muslim Masters [Basingstoke, Hampshire 2003], p. 14-36)

Lord George Goring (1608-1657), by Anthony van Dijk. “This young officer, a soldier by profession with five or six years’ experience, was the feckless eldest son of one of the Queen’s [Henrietta Maria] favourite servants, Lord Goring. As a young man he had caused his family … much anxiety … Young George … had never been troubled with religion; gaming and women were his undoing. His father had hoped that on his marriage to one of Lord Cork’s daughters he would settle down and perhaps make a career in Ireland, but the young man took neither to his wife nor his father-in-law and very soon outraged the family by departing withot notice on te best horse in the stable. He was later [1633] sent to the wars in the Netherlands to make good. Surprisingly, he did so; he had audacity, physical endurance, a quick judgment and the power to inspire his men. He had also an insinuating charm which he used to some purpose when he thought it worth his while, because, with all his wildness he was ambitious. In the two mismanaged campaigns against the Scots he had suffered the mortification of seeing his talents wasted and his ambitions checked by the incompetence of the high command. Since then, discontented with his post as governor of Portsmouth, he had intrigued to be made Lieutenant-General in the North where, should war again break out with Scotland, he believed he could conduct it with success. … [However] it suited the King and Queen better to keep him in Portsmouth. The Queen cherished baseless hopes of help from France, so that the necessity of keeping a royalist commander in the Portsmouth garrison was evident. … [In or about April 1641 Goring became involved in the so-called Army plot. His plan was more audacious than that of the other conspirators: he was for occupying London and seizing the Tower.] Some time in April George Goring, dubious about the success of the enterprise, the wisdom of his associates and the advantages to himself decided to put himself right with Parliament by betraying the plot. He sought out Lord Newport [Mountjoy Blount] and warned him of the growing conspiracy. Newport passed the information on to the Earl of Bedford … and to Lord Mandeville, … who passed it on to [leading Parliamentarian John] Pym. … Pym made no immediate use of his knowledge, knowing that its value hinged on the time at which he chose to make it public.” (C.V. Wedgwood, The King’s Peace 1637-1641, [London 1977], p. 369-371)

Filips V van Bourbon-Anjou, koning van Spanje (1700-1724, 1724-1746) “… the elaborate plans erected by the great powers fell like a house of cards from the whiff of Carlos II’s [king of Spain 1665-1700] dying breath on 1 November 1700. Carlos II’s greatest concern was to keep his lands intact, and so he contrived to avoid their partition by willing them to Louis [XIV]’s grandson, Philippe of Anjou [grandson of Louis’s wife, Maria Theresia of Austria, daughter of Philip IV of Spain]. The Spanish court had brought up Philippe’s name because he was not immediately in line for the French throne [his father and elder brother were still alive]… so granting him the Spanish inheritance would not unite France and Spain. Still, bequeathing Philippe the entire inheritance [Spain, the Spainish Netherlands, Spain’s possessions in Italy,and her colonies] would enlist Louis and the power of France to guarantee the settlement. … [Philippe’s father, the dauphin, and his brother, the duke of Burgundy] set aside their claims in favour of Philippe, making him the legitimate Bourbon candidate, and Louis accepted the will. [If the Bourbons would have refused, the Spanish would have offered the whole Spanish inheritance to Archduke Charles, the second son of Emperor Leopold I.] Throughout this manoeuvering, Louis’s goals remained essentially dynastic, that is, securing lands for his son, and later his grandson, not himself. True, the partition treaties of 1698 and 1700 would have added territory to France, but only when the dauphin succeeded Louis. Moreover, by accepting the will of Carlos II, Louis forwent any territorial addition to France, then or in the future. In fact, Louis would later insist that accepting the will was a principled and selfless act because it meant abandoning a partition treaty that would have eventually added important domains to France. Louis had probably little reasonable choice but to accept the will of Carlos II, even thogh this act would make war with the Habsburgs almost unavoidable. If he had abided by the partition treaty of 1700, which the Habsburg emperor refused to sign in any case, he would have faced a Habsburg succession and occupation in Spain. Louis would have had to fight Leopold just to gain the scraps that the treaty allowed Philip, and he would have had to attack the combined forces of Spain and the Empire to get them. And who is to say that England and the Dutch would have aided him in enforcing the treaty. By accepting the will, he would still have to fight Leopold I, but he could fight a defensive war on Spanish territory, with French and Spanish force allied against the emperor. The trick was to convince the Maritime Powers that Louis really had no choice and that his goal was purely dynastic. But Louis now misplayed his cards. After recognizing his grandson as king of Spain, Louis issued letters patent declaring that Philip retained his right to succeed to the French throne. This was not an attempt on Louis’s part to unite the crowns of France and Spain as his enemies feared. In fact Carlos’s will stipulated that the new Spanish king must reside in Madrid, and this alone made it impossible for one Bourbon to rule both countries. Louis’s decision expressed his belief that God established the principles of succession and that His choice must be honoured. … The English and Dutch probably could have lived with retaining Philip as a possible, albeit remote, claimant to the French throne, but Louis’s next move enraged William III [king of England, Scotland and Ireland, and stadhouder of the United Provinces]. The Sun King insisted on sending French troops to take over the [10] Dutch-held barrier forts in the Spanish Netherlands … From William’s perspective, losing this protective belt overturned the work of twenty years. Louis further alienated the English by having Philip V grant French Merchants the coveted asiento, the right to supply slaves to the Spanish colonies, and thus denying it to English merchants. And a final insult came when Louis acclaimed [deposed king of England] James II’s son as the legitimate king of England when the father died in September 1701. [In a certain sense the War of the Spanish Succession was also a war of the British Succession (ABdH] … A case might be made for each of these decisions in isolation, but taken as a group the appeared overbearing. Louis seemed to have gone from penitent to arrogant with his acceptance of the Spanish will. … On 15 May 1702 England, the United Provinces, and Habsburg Austria declared war on France.” (John A. Lynn, The Wars of Louis XIV 1667-1714 [London/New York 1999], p. 268-270) “in 1708 Louis mounted a naval expedition to land the Stuart claimant for the British throne in Scotland. At Dunkirk the French assembled a fleet of eight ships of the line, twenty-four frigates, and transport vessels under Chevalier de Forbin. The fleet carried twelve battalions of infantry and 13,000 fusils. 10,000 saddles and bridles, and a similar number of pistols for rebels who were expected to rise in support of the Stuart pretender [James III]. On 16 March the troops embarked, and the whole sailed a few days later, escaping the British naval forces attempting to blockade Dunkirk. On 25 March the French fleet reached the Firth of Forth, but the approach of the British fleet under Byng drove the French off before they could land the troops. The invasion fleet sailed north and attempted to put in at Inverness, but this too came to naught, and the ships sailed back to Dunkirk. Had the landings succeeded they would have, at the very least, diverted British troops from Flanders. In 1709 the French would again consider supporting an expedition to Scotland, but this scheme was shelved in January 1710 for lack of support and finances.” (id., p. 317-318)

Ongeregelde kozakken

(foto: http://www.collectie.legermuseum.nl/strategion/strategion/i008537.html) “Op Vrijdag den 3. December 1813. kwamen er reeds 40 Kozakken hier [te Dordrecht] aan, tot groote vreugde en blijdschap der lang verdrukte, en in’t laatste zeer mishandelde Burgerij, de Kozakken hielden den nacht hun verblijf in de open lucht, bij drie Vuren die door het Tusschenbestuur op het midden, der beurs [thans Scheffersplein] aangestoken waren, hunne paarden zettede zij onder de luifzels van de beurs, dik in’t stroo, waar zij zelfs op gingen leggen … de toevloed van menschen was zoo groot bij en omtrent de beurs, dat het niet te beschrijven is, zoo wel van buiten de Stad, als van de inwoners zelfs, zoo wel om onze verlossers te zien, als de vreemde woeste manier van hunne levenswijze, als mede hunne verhardheid, tegen ’t luchtgestel, als de strenge koude, die zich in dien tijd liet gevoelen, alzoo het reeds zoo hard vriesde, dat men op de binnenwaters schaatzen reed. [Op 5 dec. 1813 kwamen er 36 a 37 Kozakken terug in de stad, die op 4 dec. 1813 naar Papendrecht waren overgestoken, en bij Hardinxveld met de voorposten van de Fransen handgemeen raakten, waarbij een Kozak sneuvelde en twee gewond raakten.] hun logement wederom, als te voren, in de open lucht nemende, en door het Tusschen bestuur van al het noodige voorzien wordende, kwamen ‘er al weder een meenigte nieuwsgierige menschen van alle kanten zamenvloeijen, om die onverschrokkene ruwe schepsels te zien. [Zij zijn op 6 dec. over Zwijndrecht naar Rotterdam vertrokken.] … De Kozakken zijn hier niet lastig geweest, wat de inkwartiering betreft, want de gemeene, hebben in de open lucht gelogeerd maar kunnen geweldig veel eeten, en Jenever of andere sterken dranken drinken dat is IJsselijk; De Russische troepen zijn meer op hun gemak gesteld, en zijn over ’t algemeen zeer lastig voor de Burgers, en zuipen zo wel als de Kozakken schrikkelijk Jenever, en andere sterke dranken; de Kozakken en Jagers dronken zelfs Peper in de Jenever, met bierglazen vol, zonder eenige dronkenchap aan hun te bespeuren …” (Leendert van Es, Bombardement van Dordrecht in het Jaar 1813 (ingeleid en van commentaar voorzien door P. Breman), Dordrecht 1985, p. 43, 46-48)

Elizabeth, daughter of James I of England, Scotland and Ireland, and Anne of Denmark, about 7 years old, later married to Frederick V, elector Palatine of the Rhine, king of Bohemia (“the Winter King”, 1619-1620): “[One of the Gunpowder plotters most important objectives was the kidnapping of the nine-year-old Princess Elizabeth. The King’s daughter was house at Coombe Abbey, near Coventry … The previous year [1604] she had already proved herself capable of carrying out royal duties in nearby Coventry. … the conspirators knew that she could fulfil a ceremonial role despite her comparative youth. The ceremonial role which the Powder Treason Plotters had in mind was that of titular Queen. [Her elder brother Henry was expected to be with his father during the opening of Parliament and so would die as well. It was unsure if four-year-old Prince Charles would be present, so one of the plotters would grab him from his own separate household in London. Princess Mary, born on 9 April 1605, was considered to be too young to become a viable figurehead Queen.] (Antonia Fraser, The Gunpowder Plot [London 1996], p. 116-117)

![Discovery of the Gunpowder Plot [1605] by Henry Perronet Briggs, ca. 1823](http://www.uwstamboomonline.nl/passie/sites/fotoalbum/2147/97567.jpg)